Did you know? Negotiators are losing enormous amounts of values and opportunities at the negotiation table every single day. And you are one of them.

It’s easy to tell yourself you’re a good negotiator, but research shows even the best negotiating strategists have left huge profits behind after deals are signed. What’s happening? We found out by studying 25,000 negotiations to discover the differences in negotiation strategies between successful and unsuccessful outcomes. Based on our research, our team saw how certain details can positively or negatively influence your negotiations.1 Not knowing those details could mean the difference between a light at the end of your negotiating pathway and a sudden dead end! You don’t have to go there. Better answers are reachable! How can we make this claim?

Negotiators we surveyed went through simulation negotiations2 of varying difficulty developed since 1998. Those we surveyed were project managers, buyers, purchase managers, finance managers, IT managers, CEOs, sellers, sales managers, and technical managers. Most of them were well-educated and had a basic academic education. They came from companies within different sectors, of different sizes and with varying market positions. Their work included various types of agreements like development projects, agency agreements, consortiums, annual agreements, joint ventures, and co-operation across national borders within one organization.

Our research results sharpened our focus on why problems occur and how they can be avoided or handled. But even with new vision, we still could not explain the shadow behind success or failure. Sometimes the fundamental prerequisites for success are so badly described or imaged that no negotiation technique in the whole wide world can create any further success. And sometimes such prerequisites are so favorable that it is impossible to fail. Some negotiators are lucky while others simply run into bad luck.

In fact, one company manager told us that he only recruited lucky people. When we asked him how, within his research, he found the so-called lucky ones, he said: “We had been looking for a new sales manager and had received more than 100 applications from people who could document that they had the necessary qualifications. The first thing I did was to throw 90 of them. The ten remaining were lucky but we hired only one. He got lucky!”

But this is not about luck. Nor is knowledge the most important requisite for conducting negotiation research designed to enable successful results. In other words, our research study with its simulation exercises did not make special demands for technical, financial or trade related knowledge.

Research prerequisites were formulated to enable negotiators to reach a superior agreement to stated alternatives. Negotiation skill surfaced as the decisive factor, and the experiences we gained in the study corresponded very well with our experiences from similar real-life negotiations. This gave us provable hope that our research would lead to bright futures for negotiators.

But mistakes do happen – and the cost?

The studies showed that only two thirds of all negotiators land a deal, and it would take only one lost deal to represent about forty percent of the overall negotiation potential. This potential consisted of unused, yet realizable, added value (see NegoEconomics)3 which could have enabled the parties to reap more out of the transaction without the opponent feeling like the looser. We found that this potential represented at least part of the added value negotiations the board rooms expect when they calculate great merger gains. And as we might expect, this added value, once lost, would contribute to the combined loss of all major mergers!

Of course, it is impossible to answer how much all the mistakes cost by looking at only one instance of negotiation. But we should try to find out what can result when negotiators fail to find the most economical solution to any problem that arises during negotiation.

For example, in a negotiated agreement costing $1,000,000, the supplier gains 25 percent. Most of us would consider that to be a very nice profit, right? But what if we looked back at all the data that had been available to us during the negotiation and we surprisingly discovered we could have created $200,000 more value3 if only we had included in the agreement better offerings such as these?

- suggesting alternative payment conditions; or

- offering another delivery time; or

- changing the technical requirement specification; or

- providing improved servicing?

And let’s say that during those negotiations, the negotiators leveraged more added value,3 but, unfortunately, they used the same strategy as the average negotiators in our simulation study. Even then, as much as 40 percent of the realizable added value of $200,000 – such as $80,000 -- would remain unused. Had the seller found this $80,000, the seller alone would benefit. Seller’s profit would have grown from $250,000 to 330,000 or by as much as 32 percent.

And all of this does not yet consider that a little over one third of the negotiators who participated in the survey failed completely and never managed to enter into an agreement. In their cases, the loss of potential gain is even higher. The overall cost of all the mistakes made at the negotiation table will most likely amount to very large figures. Add to this the very negative effects like superfluous environmental destruction, poor working environments, unnecessary technical and economic risks, and the time and energy negotiators invest in debating.

But we find a positive note here -- even though the mistakes are very costly, we should not let the result depress us. Instead of focusing on the failures, we ought to look at the great potential available. The skilled negotiator has much to gain, but the critical negotiation skill must be developed. Many of our companies are not good at protecting and benefiting from the intellectual capital. The money and resources spent on developing the employees’ negotiation skills are far too low compared to the enormous potential available. That fact must be improved, but it’s a topic for later discussion.

Meanwhile, strategy matters more than time constraints!

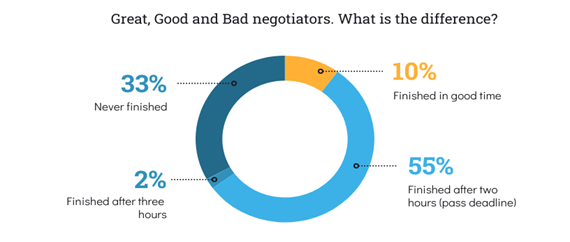

The study shows that during the 120 minutes negotiators were allowed to reach an agreement, only about 10 percent could finish without feeling any time pressure. And 55 percent did not reach an agreement until the moment when they knew time was running out. Under stress and pressed for time, they were forced to decide. Such a quandary usually does not end well…

So, when that happens -- time is almost up and negotiators are forced to reach an agreement, they too often compromise and meet other parties halfway to ensure that no one loses more than the other. Because no time remains to reconsider, they cannot be sure that all the significant points have been discussed and studied.

So, to determine how much lack of time influences the result, we gave another chance to the group of negotiators who had not reached an agreement after two hours. They were allowed to prolong the negotiation by 30 to 60 minutes. But, even so, only six percent of that group managed to reach an agreement. The others could not break their destructive pattern. Only ten percent managed to reach an agreement without getting stressed from lack of time. Nevertheless, and not surprisingly, the group that had the extra time generally created better agreements than the others, because they could use up to twenty percent more of the available negotiation potential.

The above research results prove that lack of time alone does not make the negotiation fail, but the negotiation methods are the main problem - a fact which many deny. And poor negotiation plus denial equals failure.

I must restate that during the simulation exercises we tried to step in and help the negotiators who got stuck in meaningless arguments and dead-end debates. Even though this helped, one of the parties declared: “If this had been a real negotiation situation, we would have stopped a long time ago and thrown the opponents out. We would never have accepted their behavior. But since this is an exercise, we wanted to give everyone a chance”.

To sum it up -- It is at the negotiation table that your company can win or lose great sums of money in a short time. Had these simulations been real negotiations, the risk exists that negotiators would have been even less successful.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Keld Jensen is an award-winning international author, professor, speaker, advisor and expert in negotiations, behavioral economics, and trust. The founder of the SMARTnership strategy, HIs core mission is to improve the way we collaborate by employing elevated negotiation strategies and the award winning NegoEconomics.

END NOTES

- Article titled Speakers Bureau of Canada – Keld Jensen – scroll down to Topic Presentations, page 4 to heading NEGOECONOMICS: How Two Plus Two Can Equal Forty-Two: See also article titled BigSpeak

- Definition of negotiation simulation in article titled What is negotiation simulation? by Harvard Law School

- NegoEconomics: A Vital Corporate Leadership Competency